mr. r. s. braythwayt,

esquire

What I've Learned From Failure

What I've Learned From Failure

There are a few ideas that have helped shape my evolution as a human being. I’ve written about one, Learned Optimism by Dr. Martin Seligman. Today I’m writing about another idea that was also developed by Dr. Seligman, Learned Helplessness.1

Sometimes, we feel that bad things happen to us, and we can’t prevent them. Or that our attempts to do good things for ourselves are thwarted by forces beyond our control. People describe this feeling in different ways. They may say that they are “stuck.” Or “in a rut.” To be stuck in life has nothing to do with how much money we make, or whether we are healthy, or loved, or admired.

Helplessness is the feeling that what happens to us is not under our control.

Now, obviously people feel bad when bad things happen to them. But what surprised me was that how bad we feel is more closely correlated to our feeling of helplessness, than the magnitude of the bad thing itself.

I once played a lot of backgammon and poker for money, sometimes very large sums relative to my net worth. I often lost. But it didn’t bother me, because I was convinced that I was a good player and that I won more often than I lost, and that when playing a lesser opponent, I would make larger wins when I won and lose lesser amounts when I lost.

I didn’t feel helpless about the times I’d lose a game, or a pot, or even accept a bad double and get gammoned… Even while in the box of a big chouette.

Whereas, I vividly recall being bullied about my colour in primary school. It felt like no matter what I did, the bullying continued. It was very depressing, and as we can see, that memory has never left me. But what do taunts matter? Very little, even in aggregate.

It was not the taunts that hurt a ltttle boy in 1968, it was the perception that I could do nothing about them.

To summarize, “helplessness” is a the feeling that we can’t control our own happiness. When people feel helpless about things that happen to them, it is more depressing and debilitating than the impact of the things themselves.

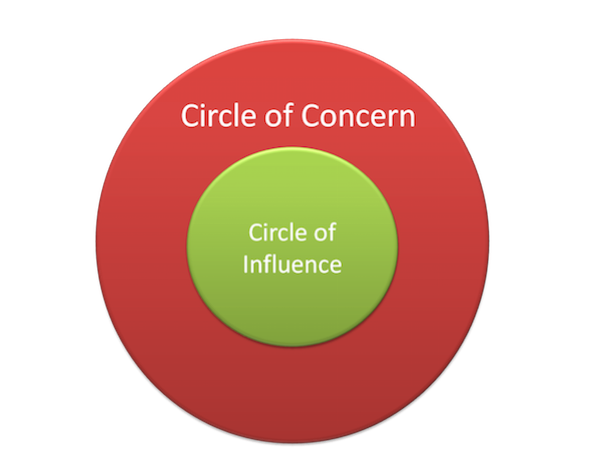

In The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen Covey wrote about a similar mechanism. He proposed the following thought exercise: Take a sheet of paper, and draw a Venn diagram on it. One circle is our “circle of concern,” it represents the things we care about. The other circle is our “circle of influence,” the things we believe we can control.

For most people, the circle of concern surrounds and envelops the circle of influence. We care about many more thaings than we believe we can change.

The difference between them represents things we care about, but believe we can’t change. This is unhealthy! We worry about such things, but feel helpless to make them better. Covey argued that we need to align the two circles, to learn how to expand our circle of influence, and also to shrink our circle of concern. When the two are in perfect alignment, we are happiest.

If “helplessness” is the feeling that we cannot control our own happiness, “learned helplessness” is helplessness that is acquired from our environment.

In learned helplessness studies, an animal is repeatedly exposed to an aversive stimulus which it cannot escape. Eventually, the animal stops trying to avoid the stimulus and behaves as if it is helpless to change the situation. When opportunities to escape become available, learned helplessness means the animal does not take any action.–Wikipedia

Seligman’s research established that helplessness can be learned, primarily by repeatedly placing the subject in a situation where bad things happen to them, and they have no control over the outcome.

To accelerate this process, we provide affordances for control, but teach the subjects that the affordances are unreliable.

For example, say we have a Prisoner, and we want to induce learned helplessness. We allow them to hatch escape plots, and even to get started on their escape, but we always catch them after they think they’ve gotten away, and thus we teach them that no matter how much control it appears they have, they don’t really have any control.

This is far worse than putting them in a prison where it appears that there is no escape. To return to the “circles” exercise, learned helplessness is the process of shrinking our circle of influence, of learning that we have far less influence than we thought.

Some environments are toxic to us through no fault of any one person. Good people gathered in a group sometimes do unfortunate things to people.

The worst such environments for us are the ones full of intelligent people with good intentions. This is like an environment where there are “false affordances.” Each person we talk to is trying to help us be happy, but none of the strategies work because the environment as a whole resists every single thing we try.

The net effect is learned helplessness, the feeling that we are powerless to effect meaningful change for ourselves or for the environment as a whole.

They may be good people, we need not crticize them as people. But we need to accept that the behaviour of a single otherwise-good person, or the behaviour of good people when embedded within a certain kind of environment, can teach us to feel helpless.

When we have people or circumstances that teach us to be helpless, we need to change ourselves, change the environment, or most drastically, separate ourselves from it.

I’m no longer accepting the things I cannot change… I’m changing things I cannot accept.

—Angela Davis

A strategy for “unstucking ourselves” is to adopt Stephen Covey’s methodology. Think about our circles of concern and influence, and consciously shrinking our circle of concern to match our perceived circle of influence.

It isn’t always a big, bad toxic person in our life, or a big, bad, toxic environment. Sometimes it’s that we have misaligned circles of concern and influence, and we are investing our energies in areas where our actions do not make us happier, so we are teaching ourselves to be helpless.

The solution may be to look hard at what we care about, and to focus on that portion that lies within our control. Sometimes that does mean a catastropic change in our environment, but often the hard work is in self-examination, in recognizing what really matters, and thus changing our behaviour so that our activities are within our circle of influence.

As we do things, and we perceive that those things effect change on things we actually care about, we unlearn our helplessness.

In Learned Optimism,2 Dr. Seligman talks about how we explain unhappy events to ourselves: Whether we think of them as “personal” or “impersonal,” whether we see them as affecting us in a “general” or “specific” way, and whether we consider the unhappy events as “permanent” or “temporary.”

Some people view adverse events as being personal to them, affecting them in a general way, and as being a permanent condition of their life. Dr. Seligman’s describes these people as pessimists. Other people view adverse events as being impersonal, specific to just one aspect of their life, and temporary. Dr. Seligman’s describes those people as optimists.

His research reveals that if we are pessimists, we can train ourselves to become optimists through Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. The basic idea is to observe the way we explain adverse events to ourselves, and then consciously re-explain them to ourselves in an optimistic way.3 Our goal is to “re-frame” adverse avents as being impersonal–not about us–rather than personal. As specific–just about one thing–rather than general. And as temporary–just right now–rather than permanent.

Consider someone who feels “stuck” professionally. They have a job, but feel unable to contribute to anything their team considers important. Their suggestions for new features and initiatives are rebuffed.

They could be pessimistic and feel that they don’t belong on the team (personal), that their career is stalled (general), and that this will continue indefinitely (permanent). In addition, having failed in their attempts to make change, they become afflicted with learned helplessness.

They could also teach themselves to see that perhaps the entire team is stuck (impersonal), that this is not about their entire career but just about what they happen to be doing at work (specific), and that the situation is changing, albeit slowly (temporary).

Helplessness is a very personal feeling. We feel helpless, but we see that others around us are not helpless. Helplessness is also a very general feeling. We feel like we’re stuck, not like we can’t solve this one thing in our life. And helplessness is a very permanent feeling. If being stuck wont last forever, we aren’t helpless, we need only be patient. We feel helpless because we fear that things will not change.

Seligman’s tactics for learning optimism are useful for unlearning helplessness. By teaching ourselves to see adverse circumstances as impersonal, specific, and temporary, we unlearn the feeling of helplessness.

Everyone has some exposure to learned helplessness. It’s not a personal thing. If you imagine that the world is full of randomly arranged people and circumstances, some of them are bound to create an environment that offer promises of making positive change, but constantly dash our hopes.

Some things in our lives are not going to respond to our attempts to make change. But only some things, it isn’t really about us being stuck, it’s this program, or this job, or even this essay.

And most things really are temporary. They change on their own. Or we eventually find the right way to fix them. Or we move on and leave them behind. The feeling that our helplessness is permanent is an illusion.

Our job is not to lament our circumstances, but to avoid becoming emotionally ensnared by them. We must either change our circumstances, or change ourselves. We cannot allow the feeling of helplessness to overwhelm our ability to teach ourselves how to unlearn that feeling of helplessness.

Because ultimately, This too shall pass.

| hacker news | edit this page |

Seligman’s research methodology has attracted a great deal of criticism, as it involved electrically shocking animals, and inducing a kind of depression. The resulting “learned helplessness” is so debilitating, that the methodology has been used by others to torture human beings. Seligman claims that his work was done to help humans avoid depression, and that is the spirit in which I encourage learning about Learned Helplessness. ↩

This isn’t the first time I’ve written about Dr. Seligman’s work: See Optimism for a very personal account of its impact on my life and career. ↩

A comprehensive training plan, undertaken under the supervsion of a qualified therapist is not the same thing as reading something and trying it out on an ad hoc basis. ↩