mr. r. s. braythwayt,

esquire

What I've Learned From Failure

What I've Learned From Failure

Jenn is brought in to take over leadership of a doomed project. It is hopelessly behind, the requirements have changed so often they are now kept on a white board instead of in a document, and the office is wallpapered with Dilbert cartoons. She’s replacing the previous manager, Scott, who was defenestrated.

When she gets to her new office, Scott is clearing out his desk. “I’ll only be a minute. By the way, I left you something” he says.

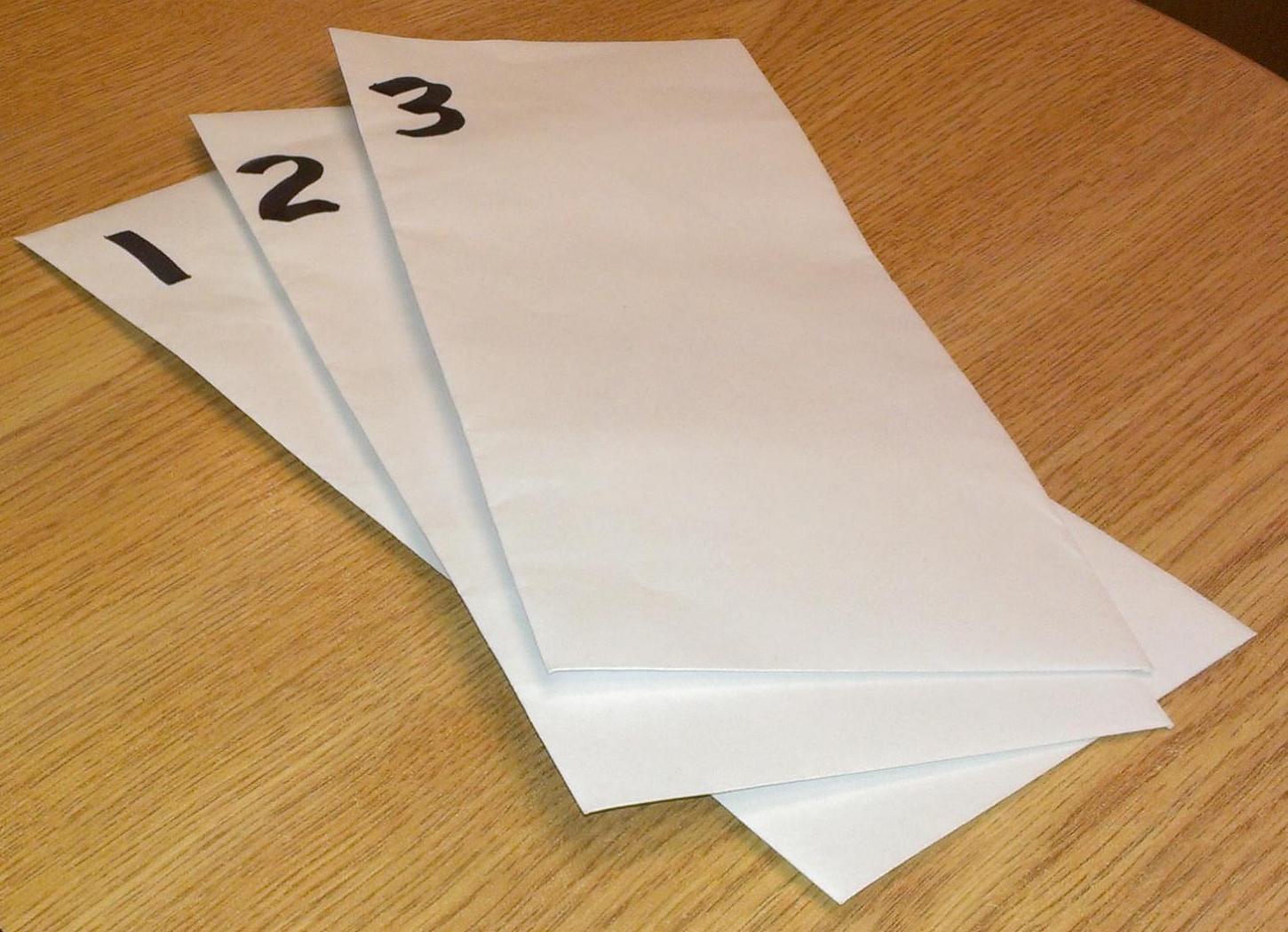

After he leaves, Jenn discovers three envelopes in the top drawer of the desk. The first envelope is labeled “Open when in trouble.” The second is labeled “Open when in even more trouble.” The third envelope is labeled “Open when all hope is lost.”

Well, she researches anti-patterns in software project leadership, has a look around, talks to everyone, identifies the key players, and goes to leadership with a clear explanation of what the problems are, what’s realistic to achieve, and what needs to be done. To her surprise, leadership seems to go along with things and tells her to make whatever changes she needs. She institutes daily builds, stand up meetings, rapid iterations, and starts tracking velocity.

Two months later, at the quarterly review, she presents her progress. The team is operating at 200% of the previous velocity, morale is up, and they’re going to get 80% of the previous functionality done with less than 90 days of slip off the impossible schedule.

There is silence, then leadership tells her that this is unacceptable. Sure, they agreed she could institute change. That’s her job. However they did not approve any compromise in scope or delivery date. This is a competitive business, and there are thousands of qualified managers looking for a job who can come in and get things done. Does Jenn want to admit she can’t do her job?

She goes back to her office in a quandary, then remembers the first envelope. Wordlessly, she opens it, and inside there is a three by five card inscribed, Blame me.

She goes back to leadership a day later with a presentation emphasizing how the project was way off track, how the architecture was FUBAR, how morale was poor, and how requirements were incorrectly documented. She doesn’t blame Scott directly, but she does identify various leadership techniques and “best practices” that were not enforced prior to her joining the project.

She commits to working with the teams to hit the dates, but she demonstrates how commitments Scott made were done without actually checking to see whether the team could deliver or making any changes to actually hit the new dates. After some huffing and puffing, leadership buys off on delivering 80% of the promised functionality with a 45 day slip in the delivery date. Whew!

Well, things go along quite well until two weeks before the original due date. Leadership calls her in and asks her to sit on the release planning board, there will be a major customer release in two weeks. She reminds them of the 45 day slip they negotiated.

“No,” they tell her baldly, “We agreed on delivering 80% of the functionality on the original date and the remaining 20% of the functionality 45 days later in release 1.1. Furthermore, we are entering into a strategic agreement with IBM and have assigned a product manager to discuss IBM WebSphere Portal integration with your technical lead.

“And the VP of Marketing needs to talk to you. We have made a strategic corporate commitment to all-singing, all-dancing web services, and he needs a forty-minute presentation explaining how your project will be implemented with web services throughout.

“You look pale. Is there a problem?”

Jenn tells leadership everything is fine, but leaves the meeting aghast.

Well, it’s back to her office and she opens the second envelope with shaking hands. The advice on the card is to reorganize.

Jenn goes back to leadership and explains that now that she’s dived deeper into the situation, she sees that the teams are not set up for success: Multiple critical projects require coördination across teams, which creates organizational and architectural impediments.

Jenn explains how reorganizing the teams around the major deliverables will align the people doing the work with the work to be done and cut the communication tax on velocity and the architectural tax on the work to be done.

Unlike her previous proposal, she doesn’t blame anyone for this. “It’s a systemic issue caused by the company’s growth.” Leadership nods along and approves the reorganization. Jenn buys extra time to reorganize, and gets back to work.

Well, the reorganization doesn’t go as well as anyone would like. Although leadership seemed enthusiastic, when it comes time to budget for necessary hires, they drag their feet on the budget. There is heavy infighting amongst managers over head-counts that undermines progress on the reorganization.

Some of the teams are eliminated, but without the necessary hires, their old responsibilities are either frozen as unowned, or distributed to unrelated teams to temporarily own. Morale amongst individual contributors crashes, and a trickle of resignations becomes a flow.

It seems that things have gone from bad to worse, and before leadership can summon Jenn to explain what’s going on, she reaches for that third envelope. She opens it, and reads Scott’s last piece of advice:

Prepare three envelopes.

This is a very, very old story. It’s often told about legendary Yankees manager Billy Martin. An earlier version of this story (with two envelopes) appeared on a predecessor to this site.